Launch from Cape Canaveral (

KSC) and

landing 1320 km southwest of San Diego in the Pacific Ocean.

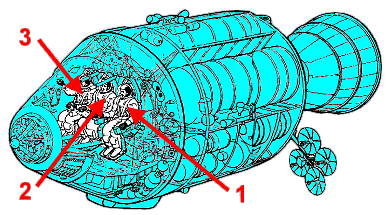

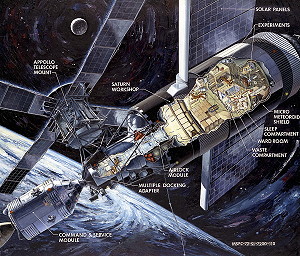

The

Skylab (SL) was a manned, orbiting spacecraft

composed of five parts, the

Apollo telescope mount (

ATM), the multiple docking adapter (MDA), the airlock

module (AM), the instrument unit (IU), and the orbital workshop (OWS). The

Skylab was in the form of a cylinder, with the

ATM being positioned 90 deg from the longitudinal axis

after insertion into orbit. The

ATM was a solar observatory, and it provided attitude

control and experiment pointing for the rest of the cluster. It was attached to

the MDA and AM at one end of the OWS. The retrieval and installation of film

used in the

ATM was accomplished by astronauts during

extravehicular activity (

EVA). The MDA served as a dock for the command and

service modules, which served as personnel taxis to the Skylab. The AM provided

an airlock between the MDA and the OWS, and contained controls and

instrumentation. The IU, which was used only during launch and the initial

phases of operation, provided guidance and sequencing functions for the initial

deployment of the

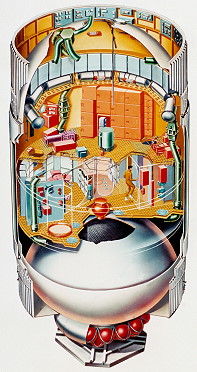

ATM, solar arrays, etc. The OWS was a modified Saturn

4B stage suitable for long duration manned habitation in orbit. It contained

provisions and crew quarters necessary to support three-person crews for

periods of up to 84 days each. All parts were also capable of unmanned,

in-orbit storage, reactivation, and reuse. The Skylab itself was launched on

May 14, 1973.

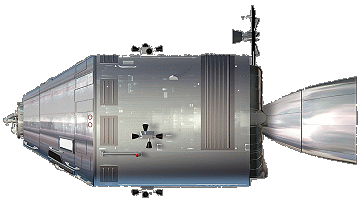

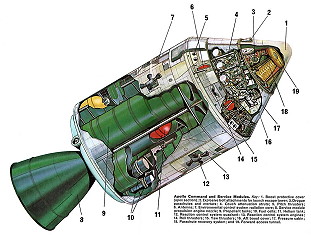

The

Command Module (CM) was a conical pressure

vessel with a maximum diameter of 3.9 m at its base and a height of 3.65 m. It

was made of an aluminum honeycomb sandwich bonded between sheet aluminum alloy.

The base of the CM consisted of a heat shield made of brazed stainless steel

honeycomb filled with a phenolic epoxy resin as an ablative material and varied

in thickness from 1.8 to 6.9 cm. At the tip of the cone was a hatch and docking

assembly designed to mate with the lunar module. The CM was divided into three

compartments. The forward compartment in the nose of the cone held the three

25.4 m diameter main parachutes, two 5 m drogue parachutes, and pilot mortar

chutes for Earth landing. The aft compartment was situated around the base of

the CM and contained propellant tanks, reaction control engines, wiring, and

plumbing. The crew compartment comprised most of the volume of the CM,

approximately 6.17 cubic meters of space. Three astronaut couches were lined up

facing forward in the center of the compartment. A large access hatch was

situated above the center couch. A short access tunnel led to the docking hatch

in the CM nose. The crew compartment held the controls, displays, navigation

equipment and other systems used by the astronauts. The CM had five windows:

one in the access hatch, one next to each astronaut in the two outer seats, and

two forward-facing rendezvous windows. Five silver/zinc-oxide batteries

provided power after the CM and SM detached, three for re-entry and after

landing and two for vehicle separation and parachute deployment. The CM had

twelve 420 N nitrogen tetroxide/hydrazine reaction control thrusters. The CM

provided the re-entry capability at the end of the mission after separation

from the Service Module.

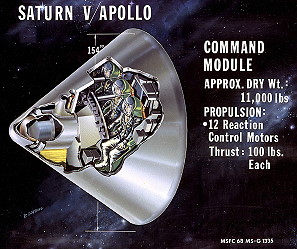

The

Service Module (SM) was a cylinder 3.9

meters in diameter and 7.6 m long which was attached to the back of the CM. The

outer skin of the SM was formed of 2.5 cm thick aluminum honeycomb panels. The

interior was divided by milled aluminum radial beams into six sections around a

central cylinder. At the back of the SM mounted in the central cylinder was a

gimbal mounted re-startable hypergolic liquid propellant 91,000 N engine and

cone shaped engine nozzle. Attitude control was provided by four identical

banks of four 450 N reaction control thrusters each spaced 90 degrees apart

around the forward part of the SM. The six sections of the SM held three

31-cell hydrogen oxygen fuel cells which provided 28 volts, two cryogenic

oxygen and two cryogenic hydrogen tanks, four tanks for the main propulsion

engine, two for fuel and two for oxidizer, and the subsystems the main

propulsion unit. Two helium tanks were mounted in the central cylinder.

Electrical power system radiators were at the top of the cylinder and

environmental control radiator panels spaced around the bottom.

This

spacecraft was almost identical to the command and service module used for

Apollo missions. Modification was made to accomodate

long-duration

Skylab missions and to allow the spacecraft to remain

semi-dormant while docked to the

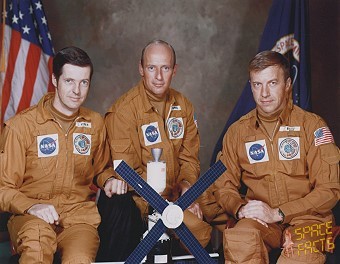

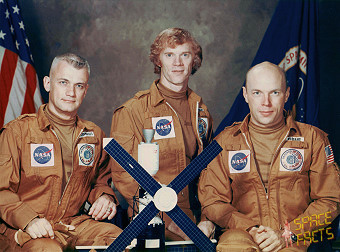

Skylab cluster. A crew of three men and their

provisions were carried. The mission of this spacecraft was to ferry a crew of

three to the

Skylab complex and return them to Earth.

This

mission carried out the

first crew of the

Skylab space station. The flight became a "rescue

mission" for the overheated space station, which had been damaged at its

launch. Launched on May 25, 1973, the first

Skylab crew's most urgent job was to repair the space

station.

Skylab's meteorite-and-sun shield and one of its solar

arrays had torn loose during launch, and the remaining primary solar array was

jammed. Without its shield,

Skylab baked in the sunshine. The crew had to work

fast, because high temperatures inside the workshop would release toxic

materials and ruin on-board film and food

The

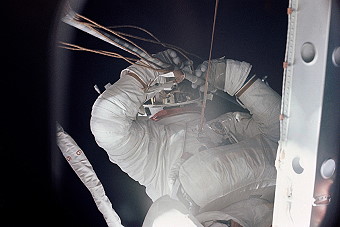

first

EVA,

in fact a SEVA, was performed by Paul

Weitz

on May 26, 1973 (0h 40m). The astronauts moved the Skylab 2 CM close to the

jammed array. Paul

Weitz

then stood with his upper body through the hatch and assembled a 4.5-m (15-ft)

pole with a shepherd's hook on the end from three 1.5-m (5-ft) sections handed

to him by Joseph

Kerwin. He hooked and pulled on the array while Joseph

Kerwin gripped his legs. Charles

Conrad had to hold the CM steady because Paul

Weitz's efforts pulled it toward the workshop. Paul

Weitz

replaced the hook with a universal prying tool when the strap did not budge,

but to no avail. Their efforts thwarted, the astronauts docked with

Skylab and closed out a 22-hour day.

On June

07, 1973 the

second spacewalk occurred (3h 25m). Joseph

Kerwin and Charles

Conrad rehearsed the planned

EVA

inside

Skylab, and on this date depressurized the

Skylab Airlock Module, which was made cramped by their

burden of tools. Charles

Conrad left the airlock through its surplus

Gemini hatch and stepped into the Pressure Garment

Assembly foot restraint at the Fixed Airlock Shroud work station. Joseph

Kerwin passed him six 1.5-m (5-ft) poles, helped him assemble

the cable cutter assembly, then moved to the discone antenna using the

ATM girders and other projections in the

EVA

Bay as mobility aids. Charles

Conrad handed him the cable cutter assembly, then moved to

the discone antenna carrying the BET. The plan called for Joseph

Kerwin to hook the cable cutter assembly on the strap holding

wing 1 closed. Charles

Conrad would then crawl down the assembly to wing 1 and

attach the BET. However, Joseph

Kerwin had difficulties finding a firm foothold near the

discone because

Skylab unexpectedly differed from the mockup in the

tank in Huntsville. He was forced to hold on with one hand while attempting to

position the pole with the other. After a frustrating half hour, Joseph

Kerwin shortened his 1.8-m (6-ft) tether by doubling it. This

held him more firmly against

Skylab and allowed him partial use of his other hand.

He finally succeeded in hooking the aluminum strap. Charles

Conrad attached the BET large hook to the discone antenna,

then climbed along the cable cutter assembly pole. He attached one of the two

BET small hooks to bolt holes on wing 1. Again, the flight

Skylab differed from the ground mockup; the second

small hook would not fit. Joseph

Kerwin tightened the BET at the discone end using a cleat,

then cut the strap holding the array closed. Charles

Conrad placed the BET over his shoulder, put his feet against

the workshop's hull, and strained against the BET to pull open the array.

Joseph

Kerwin joined him. Finally, the hydraulic damper holding the

array closed gave way.

For the

final

EVA Charles

Conrad and Paul

Weitz

left the

Skylab station on June 19, 1973 (1h 36m). The first

part of the

EVA

was very similar to the

EVA

as planned pre-flight. The astronauts removed film from the

ATM solar telescopes for return to Earth and replaced

the film. This required a fraction of the time planned. Four of

Skylab's five

EVA

work stations were positioned to restrain the astronaut during film changeout.

The Fixed Airlock Shroud (FAS) station, the main

EVA

work station, was located next to the external airlock hatch. The FAS station

was the "base camp" for ascending the ATM. The astronauts moved between the

work stations via the Deployment Assembly route, or "

EVA

Trail." The route consisted of single and dual handrails, the latter resembling

ladders without rungs. According to the

Skylab astronauts, the single handrails worked well,

while translation using the dual rails was as easy as "driving on the freeway."

All handrails were painted blue for visibility and provided with "road signs" -

alphanumeric designators. The blue faded rapidly in the strong sunlight of

space, however, and the designator labels proved difficult to see.

ATM film cassettes were moved in a device called a

film tree. The primary method of moving the trees was by three extendible booms

located in the

EVA

Bay within reach of FAS. Controls for the motorized booms were located next to

the

EVA hatch. The booms could be manually operated if

necessary, and "clotheslines," pulley-type devices, provided a backup film

transport method. Their film changeout tasks completed, Charles

Conrad and Paul

Weitz

removed space exposure samples launched on the workshop's exterior to accompany

them back to Earth. Paul

Weitz

and Charles

Conrad then moved on to tasks added after the successful wing

1 deployment on

EVA

2. They used a brush to clean the White Light Coronograph occulting disk, which

was producing glare. Charles

Conrad then moved to Circuit Breaker Relay Module 15. Acting

on instructions from the ground, he hit it with a hammer to free a stuck relay.

This low-tech solution succeeded and soon the module was feeding electricity

into the

Skylab power system again. The

EVA

brought the total for Skylab 2 to more than 5 hours, twice what was originally

planned.

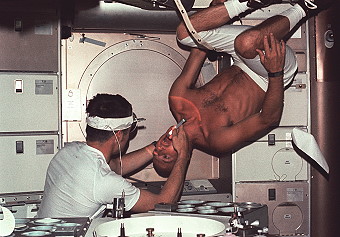

For nearly a month they made further repairs to the workshop,

conducted medical experiments, gathered solar and Earth science data, and

performed a total of 392 hours of experiments. The mission tracked two minutes

of a large solar flare with the

Apollo Telescope Mount; they took and returned some

29,000 frames of film of the sun. The

Skylab 2 astronauts spent 28 days in space, which

doubled the previous U.S. record.

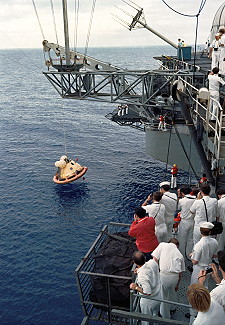

The recovery ship was the

USS

Ticonderoga.

![]()

![]()