Human Spaceflights to the Moon

![]()

International Flight No. 26Apollo 8USA |

|

|

![]()

Launch, orbit and landing data

walkout photo |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

alternative crew photo |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

alternative crew photo |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

alternative crew photo |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Crew

| No. | Surname | Given names | Position | Flight No. | Duration | Orbits | |

| 1 | Borman | Frank Frederick | CDR | 2 | 6d 03h 00m 41s | 1,5 | |

| 2 | Lovell | James Arthur, Jr. "Shaky" | CMP | 3 | 6d 03h 00m 41s | 1,5 | |

| 3 | Anders | William Alison "Bill" | LMP | 1 | 6d 03h 00m 41s | 1,5 |

Crew seating arrangement

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

Backup Crew

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

Support Crew

|

||||||||||||||||

Hardware

| Launch vehicle: | Saturn V (SA-503) |

| Spacecraft: | Apollo (CSM-103 / LTA-B) |

Flight

|

Launch from Cape Canaveral (KSC) and

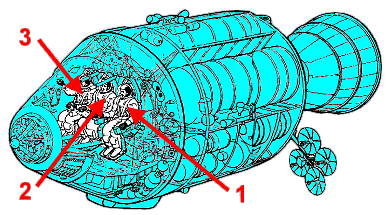

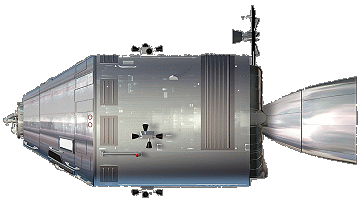

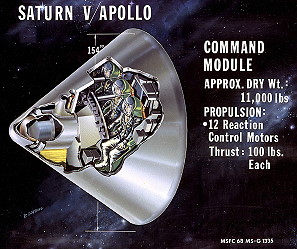

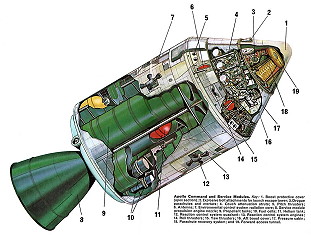

landing 1600 km southeast of Hawaii in the Pacific Ocean. The Command Module (CM) was a conical pressure vessel with a maximum diameter of 3.9 m at its base and a height of 3.65 m. It was made of an aluminum honeycomb sandwich bonded between sheet aluminum alloy. The base of the CM consisted of a heat shield made of brazed stainless steel honeycomb filled with a phenolic epoxy resin as an ablative material and varied in thickness from 1.8 to 6.9 cm. At the tip of the cone was a hatch and docking assembly designed to mate with the lunar module. The CM was divided into three compartments. The forward compartment in the nose of the cone held the three 25.4 m diameter main parachutes, two 5 m drogue parachutes, and pilot mortar chutes for Earth landing. The aft compartment was situated around the base of the CM and contained propellant tanks, reaction control engines, wiring, and plumbing. The crew compartment comprised most of the volume of the CM, approximately 6.17 cubic meters of space. Three astronaut couches were lined up facing forward in the center of the compartment. A large access hatch was situated above the center couch. A short access tunnel led to the docking hatch in the CM nose. The crew compartment held the controls, displays, navigation equipment and other systems used by the astronauts. The CM had five windows: one in the access hatch, one next to each astronaut in the two outer seats, and two forward-facing rendezvous windows. Five silver/zinc-oxide batteries provided power after the CM and SM detached, three for re-entry and after landing and two for vehicle separation and parachute deployment. The CM had twelve 420 N nitrogen tetroxide/hydrazine reaction control thrusters. The CM provided the re-entry capability at the end of the mission after separation from the Service Module. The Service Module (SM) was a cylinder 3.9 meters in diameter and 7.6 m long which was attached to the back of the CM. The outer skin of the SM was formed of 2.5 cm thick aluminum honeycomb panels. The interior was divided by milled aluminum radial beams into six sections around a central cylinder. At the back of the SM mounted in the central cylinder was a gimbal mounted re-startable hypergolic liquid propellant 91,000 N engine and cone shaped engine nozzle. Attitude control was provided by four identical banks of four 450 N reaction control thrusters each spaced 90 degrees apart around the forward part of the SM. The six sections of the SM held three 31-cell hydrogen oxygen fuel cells which provided 28 volts, two cryogenic oxygen and two cryogenic hydrogen tanks, four tanks for the main propulsion engine, two for fuel and two for oxidizer, and the subsystems the main propulsion unit. Two helium tanks were mounted in the central cylinder. Electrical power system radiators were at the top of the cylinder and environmental control radiator panels spaced around the bottom. Apollo 8 launched at 07:51:00 a.m. Eastern Standard Time on December 21, 1968, using the Saturn V's three stages, S-IC, S-II, and S-IVB, to achieve Earth orbit. The launch phase experienced only three minor problems: The engines of the first stage, S-IC, underperformed by 0.75%, causing the engines to burn for 2.45 seconds longer than planned, and toward the end of the second stage burn, S-II, the rocket underwent pogo oscillations. Frank Borman estimated the oscillations were approximately 12 hertz and ±0.25 g (±2.5 m/s²). All three rocket stages fired during launch; the S-IC and S-II detached during launch. The S-IC impacted the Atlantic Ocean at 30°12'N 74°7'W and the S-II second stage at 31°50'N 37°17'W. The third stage of the rocket, S-IVB, assisted in driving the craft into Earth orbit but remained attached to later perform the TLI burn that would put the spacecraft on a trajectory to the Moon. Once in Earth orbit, both the Apollo 8 crew and Mission Control spent the next 2 hours and 38 minutes checking that the spacecraft was in proper working order and ready for TLI. The proper operation of third stage of the rocket, S-IVB, was crucial: in the last unmanned test, the S-IVB had failed to re-ignite for TLI. Five hours after launch, Mission Control sent a command to the S-IVB booster to vent its remaining fuel through its engine bell to change the booster's trajectory. This S-IVB would then pass the Moon and enter into a solar orbit, posing no further hazard to Apollo 8. The S-IVB subsequently went into a 0.99-by-0.92-astronomical-unit (148 by 138 Gm) solar orbit with an inclination of 23.47° from the plane of the ecliptic, and an orbital period of 340.80 days. The Apollo 8 crew were the first humans to pass through the Van Allen radiation belts, which extend up to 15,000 miles (24,000 km) from Earth. Scientists predicted that passing through the belts quickly at the spacecraft's high speed would cause a radiation dosage of no more than a chest X-ray, or 1 milligray (during the course of a year, the average human receives a dose of 2 to 3 mGy). To record the actual radiation dosages, each crew member wore a Personal Radiation Dosimeter that transmitted data to Earth as well as three passive film dosimeters that showed the cumulative radiation experienced by the crew. By the end of the mission, the crew experienced an average radiation dose of 1.6 mGy. By seven hours into the mission, the crew was about one hour and 40 minutes behind flight plan due to the issues of moving away from the S-IVB and James Lovells obscured star sightings. The crew now placed the spacecraft into Passive Thermal Control (PTC), also known as "barbecue" roll. PTC involved the spacecraft rotating about once per hour along its long axis to ensure even heat distribution across the surface of the spacecraft. In direct sunlight, the spacecraft could be heated to over 200 °C (392 °F) while the parts in shadow would be -100 °C (-148 °F). These temperatures could cause the heat shield to crack or propellant lines to burst. As it was impossible to get a perfect roll, the spacecraft actually swept out a cone as it rotated. The crew had to make minor adjustments every half hour as the cone pattern got larger and larger. The first mid-course correction came 11 hours into the flight. Testing on the ground had shown that the Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine had a small chance of exploding when burned for long periods unless its combustion chamber was "coated" first. Burning the engine for a short period would accomplish coating. This first correction burn was only 2.4 seconds and added about 20.4 ft/s (6.2 m/s) velocity prograde (in the direction of travel). This change was less than the planned 24.8 ft/s (7.6 m/s) due to a bubble of helium in the oxidizer lines causing lower than expected fuel pressure. The crew had to use the small Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters to make up the shortfall. Two later planned mid-course corrections were canceled as the Apollo 8 trajectory was found to be perfect. 11 hours into the flight, the crew had been awake for over 16 hours. Before launch, NASA had decided that at least one crew member should be awake at all times to deal with any issues that might arise. Borman started the first sleep shift, but between the constant radio chatter and mechanical noises, he found sleep difficult. About an hour after starting his sleep shift, Frank Borman requested clearance to take a Seconal sleeping pill. However, the pill had little effect. Frank Borman eventually fell asleep but then awoke feeling ill. He vomited twice and had a bout of diarrhea that left the spacecraft full of small globules of vomit and feces that the crew cleaned up to the best of their ability. Frank Borman initially decided that he did not want everyone to know about his medical problems, but James Lovell and William Anders wanted to inform Mission Control. The crew decided to use the Data Storage Equipment (DSE), which could tape voice recordings and telemetry and dump them to Mission Control at high speed. After recording a description of Frank Borman's illness they requested that Mission Control check the recording, stating that they "would like an evaluation of the voice comments". The Apollo 8 crew and Mission Control medical personnel held a conference using an unoccupied second floor control room (there were two identical control rooms in Houston on the second and third floor, only one of which was used during a mission). The conference participants decided that there was little to worry about and that Frank Borman's illness was either a 24-hour flu, as Frank Borman thought, or a reaction to the sleeping pill. Researchers now believe that he was suffering from space adaptation syndrome, which affects about a third of astronauts during their first day in space as their vestibular system adapts to weightlessness. Space adaptation syndrome had not been an issue on previous spacecraft (Mercury and Gemini), as those astronauts were unable to move freely in the comparatively smaller cabins of those spacecraft. The increased cabin space in the Apollo Command Module afforded astronauts greater freedom of movement, contributing to symptoms of space sickness for Frank Borman and, later, astronaut Russell Schweickart during Apollo 9. At about 55 hours and 40 minutes into the flight, the crew of Apollo 8 became the first humans to enter the gravitational sphere of influence of another celestial body. In other words, the effect of the Moon's gravitational force on Apollo 8 became stronger than that of the Earth. At the time it happened, Apollo 8 was 38,759 miles (62,377 km) from the Moon and had a speed of 3,990 ft/s (1,220 m/s) relative to the Moon. This historic moment was of little interest to the crew since they were still calculating their trajectory with respect to the launch pad at Kennedy Space Center. They would continue to do so until they performed their last mid-course correction, switching to a reference frame based on ideal orientation for the second engine burn they would make in lunar orbit. It was only 13 hours until they would be in lunar orbit. At 64 hours into the flight, the crew began to prepare for Lunar Orbit Insertion-1 (LOI-1). This maneuver had to be performed perfectly, and due to orbital mechanics had to be on the far side of the Moon, out of contact with the Earth. After Mission Control was polled for a Go/No Go decision, the crew was told at 68 hours, they were Go and "riding the best bird we can find". At 68 hours and 58 minutes, the spacecraft went behind the Moon and out of radio contact with the Earth. The SPS ignited at 69 hours, 8 minutes, and 16 seconds after launch and burned for 4 minutes and 13 seconds, placing the Apollo 8 spacecraft in orbit around the Moon. The crew described the burn as being the longest four minutes of their lives. If the burn had not lasted exactly the correct amount of time, the spacecraft could have ended up in a highly elliptical lunar orbit or even flung off into space. If it lasted too long, they could have impacted the Moon. After making sure the spacecraft was working, they finally had a chance to look at the Moon, which they would orbit for the next 20 hours. On Earth, Mission Control continued to wait. If the crew had not burned the engine or the burn had not lasted the planned length of time, the crew would appear early from behind the Moon. However, this time came and went without Apollo 8 reappearing. Exactly at the calculated moment, the signal was received from the spacecraft, indicating it was in a 193.3-by-69.5-mile (311.1 by 111.8 km) orbit about the Moon. As they rounded the Moon for the ninth time, the second television transmission began. Frank Borman introduced the crew, followed by each man giving his impression of the lunar surface and what it was like to be orbiting the Moon. Frank Borman described it as being "a vast, lonely, forbidding expanse of nothing." Then, after talking about what they were flying over, William Anders said that the crew had a message for all those on Earth. Each man on board read a section from the Biblical creation story (verses 1-10) from the Book of Genesis. Frank Borman finished the broadcast by wishing a Merry Christmas to everyone on Earth. His message appeared to sum up the feelings that all three crewmen had from their vantage point in lunar orbit. Frank Borman said, "And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth". The only task left for the crew at this point was to perform the Trans-Earth Injection (TEI), which was scheduled for 2½ hours after the end of the television transmission. The TEI was the most critical burn of the flight, as any failure of the SPS to ignite would strand the crew in Lunar orbit, with little hope of escape. As with the previous burn, the crew had to perform the maneuver above the far side of the Moon, out of contact with Earth. Before the re-entry there was a minor error in the course hours before the scheduled splashdown in the Pacific, but that was corrected. The landing was only 2.6 km from the target point away. The crew was recovered by the USS Yorktown. |

Photos / Graphics

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

more Moon observation photos |

|

| © |  |

Last update on August 11, 2020.  |

|