Human Orbital Spaceflights

![]()

International Flight No. 29Apollo 9USA |

|

|

![]()

Launch, orbit and landing data

walkout photo |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

alternative crew photo |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

alternative crew photo |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

alternative crew photo |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Crew

| No. | Surname | Given names | Position | Flight No. | Duration | Orbits | |

| 1 | McDivitt | James Alton | CDR | 2 | 10d 01h 00m 53s | 151 | |

| 2 | Scott | David Randolph | CMP | 2 | 10d 01h 00m 53s | 151 | |

| 3 | Schweickart | Russell Louis "Rusty" | LMP | 1 | 10d 01h 00m 53s | 151 |

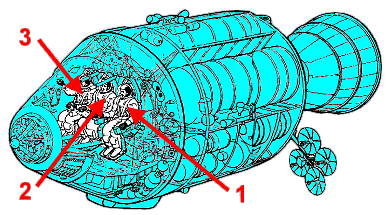

Crew seating arrangement

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

Backup Crew

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

Support Crew

** replaced Mitchell on November 13, 1968 |

|||||||||||||||||||

Hardware

| Launch vehicle: | Saturn V (SA-504) |

| Spacecraft: | Apollo (CSM-104 „Gumdrop“ / LM-3 „Spider“) |

Flight

|

Launch from Cape Canaveral and landing close

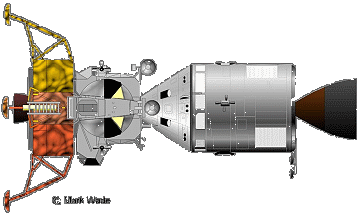

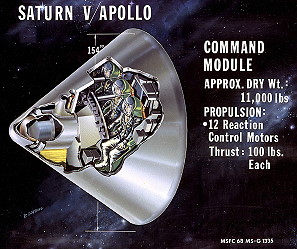

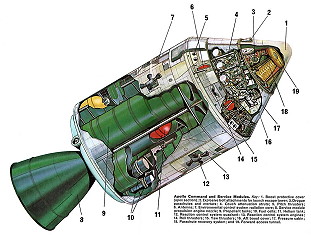

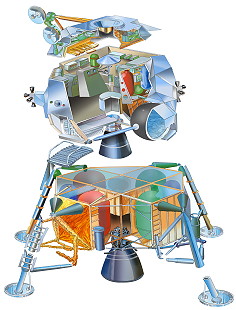

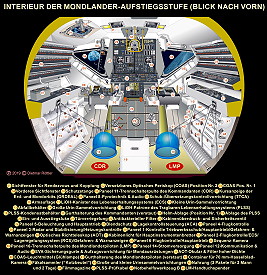

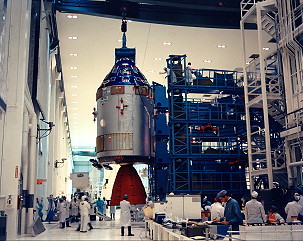

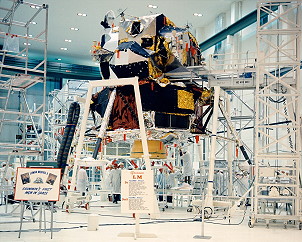

to the Bermuda Islands in the Atlantic Ocean. Originally Clifton Williams was the lunar module pilot for the backup crew. He died on October 05, 1967, in a T-38 crash. His spot was given to Alan Bean. Later, when the backup crew flew Apollo 12, a fourth star was added to their mission patch in remembrance of him. The Command Module (CM) was a conical pressure vessel with a maximum diameter of 3.9 m at its base and a height of 3.65 m. It was made of an aluminum honeycomb sandwich bonded between sheet aluminum alloy. The base of the CM consisted of a heat shield made of brazed stainless steel honeycomb filled with a phenolic epoxy resin as an ablative material and varied in thickness from 1.8 to 6.9 cm. At the tip of the cone was a hatch and docking assembly designed to mate with the lunar module. The CM was divided into three compartments. The forward compartment in the nose of the cone held the three 25.4 m diameter main parachutes, two 5 m drogue parachutes, and pilot mortar chutes for Earth landing. The aft compartment was situated around the base of the CM and contained propellant tanks, reaction control engines, wiring, and plumbing. The crew compartment comprised most of the volume of the CM, approximately 6.17 cubic meters of space. Three astronaut couches were lined up facing forward in the center of the compartment. A large access hatch was situated above the center couch. A short access tunnel led to the docking hatch in the CM nose. The crew compartment held the controls, displays, navigation equipment and other systems used by the astronauts. The CM had five windows: one in the access hatch, one next to each astronaut in the two outer seats, and two forward-facing rendezvous windows. Five silver/zinc-oxide batteries provided power after the CM and SM detached, three for re-entry and after landing and two for vehicle separation and parachute deployment. The CM had twelve 420 N nitrogen tetroxide/hydrazine reaction control thrusters. The CM provided the re-entry capability at the end of the mission after separation from the Service Module. The Service Module (SM) was a cylinder 3.9 meters in diameter and 7.6 m long which was attached to the back of the CM. The outer skin of the SM was formed of 2.5 cm thick aluminum honeycomb panels. The interior was divided by milled aluminum radial beams into six sections around a central cylinder. At the back of the SM mounted in the central cylinder was a gimbal mounted re-startable hypergolic liquid propellant 91,000 N engine and cone shaped engine nozzle. Attitude control was provided by four identical banks of four 450 N reaction control thrusters each spaced 90 degrees apart around the forward part of the SM. The six sections of the SM held three 31-cell hydrogen oxygen fuel cells which provided 28 volts, two cryogenic oxygen and two cryogenic hydrogen tanks, four tanks for the main propulsion engine, two for fuel and two for oxidizer, and the subsystems the main propulsion unit. Two helium tanks were mounted in the central cylinder. Electrical power system radiators were at the top of the cylinder and environmental control radiator panels spaced around the bottom. The lunar module (LM) was a two-stage vehicle designed for space operations near and on the Moon. The spacecraft mass of 15,065 kg was the mass of the LM including astronauts, propellants and expendables. The dry mass of the ascent stage was 2180 kg and it held 2639 kg of propellant. The descent stage dry mass was 2034 kg and 8212 kg of propellant were onboard initially. The ascent and descent stages of the LM operated as a unit until staging, when the ascent stage functioned as a single spacecraft for rendezvous and docking with the command and service module (CSM). The descent stage comprised the lower part of the spacecraft and was an octagonal prism 4.2 meters across and 1.7 m thick. Four landing legs with round footpads were mounted on the sides of the descent stage and held the bottom of the stage 1.5 m above the surface. The distance between the ends of the footpads on opposite landing legs was 9.4 m. One of the legs had a small astronaut egress platform and ladder. A one meter long conical descent engine skirt protruded from the bottom of the stage. The descent stage contained the landing rocket, two tanks of aerozine 50 fuel, two tanks of nitrogen tetroxide oxidizer, water, oxygen and helium tanks and storage space for the lunar equipment and experiments, and in the case of Apollo 15, 16, and 17, the lunar rover. The descent stage served as a platform for launching the ascent stage and was left behind on the Moon. The ascent stage was an irregularly shaped unit approximately 2.8 m high and 4.0 by 4.3 meters in width mounted on top of the descent stage. The ascent stage housed the astronauts in a pressurized crew compartment with a volume of 6.65 cubic meters which functioned as the base of operations for lunar operations. There was an ingress-egress hatch in one side and a docking hatch for connecting to the CSM on top. Also mounted along the top were a parabolic rendezvous radar antenna, a steerable parabolic S-band antenna, and 2 in-flight VHF antennas. Two triangular windows were above and to either side of the egress hatch and four thrust chamber assemblies were mounted around the sides. At the base of the assembly was the ascent engine. The stage also contained an aerozine 50 fuel and an oxidizer tank, and helium, liquid oxygen, gaseous oxygen, and reaction control fuel tanks. There were no seats in the LM. A control console was mounted in the front of the crew compartment above the ingress-egress hatch and between the windows and two more control panels mounted on the side walls. The ascent stage was launched from the Moon at the end of lunar surface operations and returned the astronauts to the CSM. The descent engine was a deep-throttling ablative rocket with a maximum thrust of about 45,000 N mounted on a gimbal ring in the center of the descent stage. The ascent engine was a fixed, constant-thrust rocket with a thrust of about 15,000 N. Maneuvering was achieved via the reaction control system, which consisted of the four thrust modules, each one composed of four 450 N thrust chambers and nozzles pointing in different directions. Telemetry, TV, voice, and range communications with Earth were all via the S-band antenna. VHF was used for communications between the astronauts and the LM, and the LM and orbiting CSM. There were redundant transceivers and equipment for both S-band and VHF. An environmental control system recycled oxygen and maintained temperature in the electronics and cabin. Power was provided by 6 silver-zinc batteries. Guidance and navigation control were provided by a radar ranging system, an inertial measurement unit consisting of gyroscopes and accelerometers, and the Apollo guidance computer. Apollo 9 was the first space test of the complete Apollo spacecraft, including the third critical piece of Apollo hardware besides the Command & Service Module (CSM) and the Saturn V launch vehicle - the Lunar Module (LM). It was also the first space docking of two vehicles with an internal crew transfer between them. For ten days, the astronauts put both Apollo spacecraft through their paces in Earth orbit, including an undocking and redocking of the lunar lander with the command vehicle, just as the landing mission crew would perform in lunar orbit. Apollo 9 gave proof that the Apollo spacecraft were up to this critical task, on which the lives of lunar landing crews would depend. The crews of this and the following Apollo missions were allowed to name their own spacecraft (that happened the last time with Gemini 3). The gangly lunar module was named "Spider", and the command module was labelled "Gumdrop" on account of the blue cellophane wrapping in which the craft arrived at KSC. After launch and injection of the combined S-IVB stage and the adaptor-LM-CSM payload into a 189.6 x 192.5 km Earth orbit, the S-IVB propellant tanks were vented, changing the orbit to 198 x 204 km. At 2:41 after launch the CSM separated from the S-IVB and the adaptor panels were jettisoned, exposing the LM mounted on the S-IVB. The CSM turned around and docked with the LM at 3 hours after launch. At 4 hours after launch the S-IVB and CSM-LM were separated and the S-IVB had a 62 second burn to raise its apogee to 3050 km. Over the next few days, the CSM service propulsion system (SPS) was fired five times to change the orbit to prepare for rendezvous maneuvers and test the dynamics of the CSM and LM under thrust. The LM descent engine was also fired for 367 seconds on March 06, 1969. Apollo 9, the third manned mission in the American Apollo space program, was the first flight of the Command/Service Module (CSM) with the Lunar Module (LM). Its three-person crew, consisting of Commander James McDivitt, Command Module Pilot David Scott, and Lunar Module Pilot Russell Schweickart, tested several aspects critical to landing on the Moon, including the LM engines, backpack life support systems, navigation systems, and docking maneuvers. The mission was the second manned launch of a Saturn V rocket. An EVA was performed on March 06, 1969 by Russell Schweickart (0h 46m), checking out the new Apollo spacesuit, the first to have its own life support system. His only connection to the LM was a 25-foot (7.62 meters) nylon rope to keep him from drifting into space. Russell Schweickart walked between the LM and CSM hatches, maneuvered on handrails, took photographs, and described rain squalls over KSC; David Scott in a stand-up-EVA (0h 46m) filmed him from the command module hatch. On March 07,1969 with James McDivitt and Russell Schweickart in the LM, David Scott separated the CSM from the LM and fired the reaction control system thrusters to obtain a distance of 5.5 kilometers between the two spacecraft. Both astronauts then performed a lunar module active rendezvous. The LM successfully docked with the CSM after being up to 183.5 kilometers away from it during the six-and-one-half-hour separation. After James McDivitt and Russell Schweickart returned to the CSM, the LM ascent stage was jettisoned. The crew performed also additional scientific work (i.e. photography of Earth surface). All the main goals of this mission were successfully accomplished. As a result of unfavorable weather in the planned landing area, Apollo 9 completed an additional orbit before returning to Earth. The crew was recovered by the USS Guadalcanal. |

EVA data

| Name | Start | End | Duration | Mission | Airlock | Suit | |

| EVA | Schweickart, Russell | 06.03.1969, 16:?? UTC | 06.03.1969, 17:?? UTC | 0h 46m | Apollo 9 | A7L No. 15 | |

| SEVA | McDivitt, James | 06.03.1969, 16:?? UTC | 06.03.1969, 17:?? UTC | 0h 46m | Apollo 9 | A7L No. 20 | |

| SEVA | Scott, David | 06.03.1969, 16:?? UTC | 06.03.1969, 17:?? UTC | 0h 46m | Apollo 9 | A7L No. 19 | |

Photos / Graphics

|

|

|

Source: www.astronautix.com/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

more Earth observation photos |

|

more EVA photos |

|

| © |  |

Last update on August 11, 2020.  |

|